His life was short and his scientific accomplishments modest, but Bruce Frederick Cummings’ personal journal made a lasting impact on Andrew Katsis.

Model Specimens is a monthly column that explores the role models who inspired today's scientists. This month, Life Science Editor Andrew Katsis shares how Bruce Frederick Cummings taught him how to come to grips with grief.

November 3, 1908. Hunched over a table in his attic, scalpel in hand, Bruce Frederick Cummings begins to dissect a sea urchin. He carefully slices open the specimen to reveal, for the first time in his life, Aristotle’s lantern – a structure of plates and muscles that form part of the urchin’s mouth organs. He is thrilled at the sheer perfection of this structure, a complex mechanism shaped by aeons of evolution.

But his scientific curiosity comes at a cost: under the lens of objective analysis, even the greatest wonders of nature seem to lose some of their beauty. “The sunset becomes waves of light impinging on atmospheric dust; the most beautiful pearl, the encysted itch of a mollusc,” he later lamented. We can have beauty or knowledge, but not both.

Cummings was a natural-born naturalist. He spent his boyhood years roaming the countryside around his family home in Devon, England, chasing squirrels and collecting bird eggs. He took careful notes to record his nature observations, and no animal was too insignificant to warrant his fascination. His journal begins, at age 13, with the following matter-of-fact declaration:

Am writing an essay on the life history of insects and have abandoned the idea of writing on ‘How Cats Spend their Time’.

Cummings lived to explore and understand the natural world. In his early teenage years, he trapped birds and catalogued their nests during the breeding season. “It is a pastime of sheer delight, with naught but beautiful dreams and lovely thoughts,” he wrote in his journal on April 2, 1903. A few years later, he fell in love with dissections, and would rise at 6 o’clock every morning to pick apart his latest zoological specimen. During the course of his amateur studies, Cummings dissected a leech, a frog, an eel, a sheldrake, a corncrake and a dogfish. He once walked home, proudly clutching a horse’s skull that he had procured from the local veterinary surgeon.

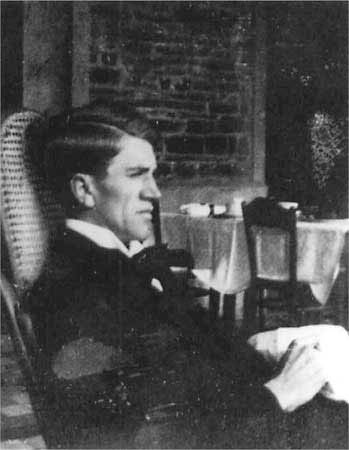

Cummings as a boy, potentially pondering how cats spend their time. Old Grey Poet (Public Domain Mark 1.0)

Whenever I read The Journal of a Disappointed Man – Cummings’ collection of diary entries published under the nom de plume WNP Barbellion – I see a lot of myself in him. In my younger years, I also spent hours chasing the nature in my backyard. Not with the same dedication as Cummings, admittedly, but a bird did once spray me with faeces while I tried to access her nestlings. Over the years, I kept blue-tongued lizards, yabbies and tadpoles with varying degrees of success, and once startled my sister by entering the house joyfully waving around an emu leg.

We are both prolific diarists, as well, with a similarly wry literary style. For his part, Cummings’ writing is thoughtful and colourful; on different days, and even within the same journal entry, he wavers between egotism and self-deprecation. He is a little shy, and finds social interactions irksome. “I like zoology,” he once wrote. “I wish I could do without zoologists”.

Cummings was initially discouraged from pursuing his passion for nature, and instead “signed [his] death warrant” by following his father into journalism. Nevertheless, he eventually found a position at what is now the Natural History Museum in London, where he worked mostly with invertebrates. Here, his zoological accomplishments were modest: he published several dozen specialised scientific papers, including a letter in Nature rejecting the idea that newts navigate by perceiving moisture at a distance. He kept a photograph of the 19th century anatomist Thomas Henry Huxley, perhaps his greatest zoological idol, on the mantelpiece.

Nowadays, try as I might, I can’t help but associate Cummings with death. One reason for this is that I first encountered his journal shortly after the loss of my grandmother, who died in 2012 following a year-long struggle with cancer. At the time, I had yet to come to terms with the slippery notion of dying; being a lifelong atheist, the usual platitudes didn’t seem to apply. What comfort can we possibly glean from an eternity of nothingness?

"Language cannot express the joy and happy forgetfulness during a ramble in the country." Old Grey Poet (Public Domain Mark 1.0)

Reading Cummings’ journal for the first time, he seemed to understand death more profoundly than most people. In November 1915, at age 26, he was called to enlist in the British Army, but was rejected after only a brief medical examination. On the train home, curious, he opened a confidential letter from his physician, and learnt what his family had been keeping from him: he had multiple sclerosis, and was not expected to reach his thirtieth year.

From that moment, Cummings became less interested in natural history and more into documenting the emotional turmoil of being trapped inside a failing body. “I am over 6 feet high and as thin as a skeleton; every bone in my body, even the neck vertebras, creak at odd intervals when I move,” he wrote in a characteristic journal entry. “Even as I sit and write, millions of bacteria are gnawing away my precious spinal cord, and if you put your ear to my back the sound of the gnawing I dare say could be heard”.

Yet even as his own end loomed, Cummings didn’t cling blindly to fanciful notions of an afterlife. His childhood belief in the Bible had been eroded, and as an adult he described himself as agnostic – not surprisingly, given his admiration for Huxley, who had coined the term. Instead, throughout his life Cummings seemed to find solace in science:

To me the honour is sufficient of belonging to the universe — such a great universe, and so grand a scheme of things. Not even Death can rob me of that honour. For nothing can alter the fact that I have lived; I have been I, if for ever so short a time. And when I am dead, the matter which composes my body is indestructible — and eternal, so that come what may to my 'Soul,' my dust will always be going on, each separate atom of me playing its separate part — I shall still have some sort of a finger in the pie. When I am dead, you can boil me, burn me, drown me, scatter me — but you cannot destroy me: my little atoms would merely deride such heavy vengeance. Death can do no more than kill you.

In this passage, one of the most affecting I’ve ever read, Cummings brings his scientific eye to the question of life and death. He had dissected enough organisms in his life to appreciate the transience of flesh, yet in the indestructibility of the atom he found a kind of immortality. His words offer me comfort whenever I think about the loved ones I’ve lost over the years – a way to hold onto the deceased for just a little longer without betraying my scientific ideals. “Under the lens of scientific analysis, natural beauty disappears,” Cummings wrote; but here, at least, he created a space where science and beauty were mutually compatible.

"I am lonely, penniless, paralysed, and just turned twenty-eight. But I snap my fingers in your face and with equal arrogance I pity you. I pity you your smooth-running good luck and the stagnant serenity of your mind. I prefer my own torment. I am dying, but you are already a corpse. You have never really lived." Old Grey Poet (Public Domain Mark 1.0)

Of course, I don’t want to pretend that Cummings had all of the answers. Rereading his journal entries recently, I realised that he was as fearfully uncertain about death as any of us. On January 21, 1917, he even envisions a Heaven-like afterlife in which a person’s spirit spends an eternity reliving its most cherished memories. Only a month later, he confesses his complete ignorance on the matter, asserting that “it is futile and presumptuous for me to opine anything about the next world.” Although Cummings seems a little shameful about this lack of conviction, I admire his humility – after all, there’s nothing more scientific than admitting “I don’t know”.

The Journal of a Disappointed Man was published in March 1919, complete with a preface by HG Wells. Cummings lived long enough to see his book become a success, but died in October that year, shortly after his thirtieth birthday. “I have telescoped into those few years a tolerably long life,” he wrote in his journal. “I have loved and married, and have a family; I have wept and enjoyed, struggled and overcome, and when the hour comes I shall be content to die”.

Three days after his death, Cummings’ body was cremated. His ashes were interred at London’s Golders Green Crematorium until 1980, when they were removed for burial. We can only presume that, just as he predicted, his atoms persist to this day.

Edited by Nicola McCaskill and Tessa Evans